Results

The results of the U.S. Pacific submarine campaign were really three fold. Merchant marine losses crippled Japan’s direct industrial ability to build war machines. As Japan was (and is) a net importer of food, losses in food stuffs and the resulting severe rationing indirectly weakened industrial capabilities. The lack of indigenous. transport capabilities meant the loss of commercial transport capability, which the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army relied on, severely restricted the Japanese ability to reinforce anywhere in the Pacific. Lack of shipping also restricted IJA actions in China as more and more resources were sunk or diverted to support the Home Islands. This also allowed offensive ground and naval operations by Allied forces. Further more, the cost of building replacement shipping, escort vessels, as well as loss of naval power cost Japan the ability to spend resources and money to expand war making capabilities.

Direct results of submarine campaign against Japan by the United States Navy became fairly well known. Japan began 1942 with approximately 6 million tons of merchant shipping. From 1942 through August 1945, Japan’s ship yards built an additional 3 million tons of merchant shipping. Records of Japanese ships sunk were not well kept, so the Joint Army Navy Assessment Committee (JANAC) verified sinkings become the benchmark to judge by.[1]

Of the total 9 million tons of merchant shipping built by Japan by August of 1945, less than 1 million tons were afloat by 15 August 1945 upon cessation of offensive actions by U.S. naval forces. Roughly 1 million more tons were in shipyards in some state of repair. Whether this tonnage counts as Japanese losses is debatable. JANAC records that 8.1 million tons of Japanese Merchant Marine vessels were sunk by Allied forces during the war.[2] Submarines of the United States Navy sank 4.9 million tons or 60% of those losses. An additional 700,000 tons of Imperial Japanese Navy vessels[3] were sent to the bottom by American submarines bringing the total tonnage credited to U.S.N. submarines to 5.6 million tons[4]. With these shipping losses go the crew casualties. Japan’s merchant fleet began the war with 122,000 merchant seamen. Of the 116,000 casualties, 69,600 were administered by U.S. submarines [5].

This by a force 288 submarines[6]. Of this force of 288, fifty two were lost (sunk or grounded) with forty eight of those being in the Pacific with 3,617 officers and crew lost with them[7]. That gives the submarine forces, comprising 1.6% of the manpower of the U.S. Navy a loss rate of 22%, the highest in the United States Armed Forces[8]. While the German U-boat loss rate was much higher and the numbers deployed were four times what America fielded, the average number of ships sunk per submarine by the United States Navy was 4.88 per boat while the U-boats sank 2827 Allied ships sunk by a total of 1159 U-boats (not all deployed, just like the U.S. submarines) gave 2.44 ships sunk per U-boat.[9]

Why wasn’t more of this known? The confidentiality of submarine operations purposely hid the effectiveness of our submarine forces. This was done to prevent the enemy from learning of the methods used by U.S.N submarines that worked or did not work, as well as prevent the Japanese from learning the effectiveness of their ASW efforts.[10]

An unfortunate side effect of this was reflected in the lack of awards to the submarine force. Still, due to commanders like Lockwood and Christie, seven Medals of Honor were received by deserving officers. The submarine crews earned 49 Presidential Unit Citations and 52 Navy Unit Citations. Many commanders received Navy Crosses, Silver Stars, and Bronze Stars for the total crew efforts. Yet individual awards to deserving crewmen and officers not in command were rare.[11]

Another side effect of belated knowledge of the submarine forces effectiveness was second guessers. Many so called experts concluded that the invasions of the Palaus., the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa were unnecessary. The fire bombing and use of the atom bombs were like wise unnecessary.[12]

Japanese records show this to be a fallacy. In August 1943, Emperor Hirohito called for both the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) to conduct studies of the prospect of the war. In October 1943 the Naval Staff reported the war was irretrievably lost. All territories gained since 1880 would be forfeit. The Army general Staff’s report was less optimistic. They predicted if the war was continued, Japan itself would be literally decimated.[13]

Faced with this, Emperor Hirohito, the Cabinet, and his Privy Council concluded surrender was not possible. The Bushido could not afford to give up. More importantly to these players, politics could not afford to give up while the death toll for Japan was only 100,000. If the emperor surrendered with only one hundred thousand dead, their deaths would be in vain. To preserve the emperor’s divinity, millions must die. Then the emperor could surrender as a act of mercy to spare further suffering. To keep the emperor safe and allow this plan to unfold, the IJN and IJA planned for the suicidal defense of the nation. Prince Konoye, with full knowledge of this, was ordered to head a false peace delegation. His mission was to misdirect American efforts and hopefully save the emperor’s position.[14]

The obvious. effects of the lack of unified command on the submarine war efforts was not forgotten. Following the victory in the Pacific, the necessity to realign the chains of command became glaring[15]. Eventually, the United States Pacific Fleet chain of command became CINCPACFLT (Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet) reporting to CINCPAC (Commander in Chief, Pacific), along with PACAF and the Army’s Pacific forces in what is now referred to as a unified command. The World War II numbered fleets were also reorganized. First Fleet consisted of ships in the Eastern Pacific and called San Diego home port. Third Fleet home ported out of Pearl Harbor and maintained control over vessels in the mid Pacific. Seventh Fleet took its new home port in Yokosuka, Japan and ruled the western Pacific and Indian Ocean. When the Fifth Fleet was reconstituted in the 1990s, its purview became the Arabian Gulf. Areas of operations and responsibilities were delineated with definite central chain of command.

While each fleet now had its own commander of submarines, all submarines were and are centrally controlled by COMSUBPAC. COMSUBPAC then could allocate actual submarines to each fleet for area directed operations or be tasked by COMSUBPAC with using a submarine provided by COMSUBPAC for a COMSUBPAC mission. Centralized strategy would not require direct intervention from the CNO.

CDR Michel Thomas Poirier lists what he terms “hidden costs” in his 1999 treatises, “Results of the German and American Submarine Campaigns of World War II.”, and “Results of the American Pacific Submarine Campaign of World War II.”. Aside from the obvious. ships lost, Poirier cites the loss of cargo, shipyard production for other needs, loss of ability to reinforce the Army and loss of strategic materials needed to continue the war. While these seem obvious. now, they are not normally included. One of Poirier’s better insights is the cost ratio. Poirier totals the cost of building the 288 submarines by American and balances that against the cost of the ASW minefield, ASW aircraft, escort ships, and replacement shipping[16]. These include time lost as ships waited for convoys to form[17]. ADM Oikawa forced to form larger convoys by Feb 1944.[18]

A blatant display of the results of the submarine campaign were shown by Japan during the war. While Japanese treatment of POWs was horrific at best, even worse treatment was reserved for those inflicting more effective losses on Japan. The B-29 “terror fliers” endured far worse treatment than regular POWs, as War Criminals. Submariners captured were treated even worse. Special treatment saved for captured submariners included torture, beatings, slave labor, cannibalism by their captors, and as stated before in Manning Kimmel’s tale, summary execution in horrific fashion.[19]

Analysis

As almost every author on the U.S.N. submarines in the Pacific has noted, there was no unified strategy or command. Even when ADM King intervened directing blockade, King’s own desires to change the path of Macarthur’s forces to Taiwan drove his plan more than the idea of strangling Japan.

Further results of the United States’ submarine campaign affect the U.S. Navy (and the military as a whole) today.

Conclusion

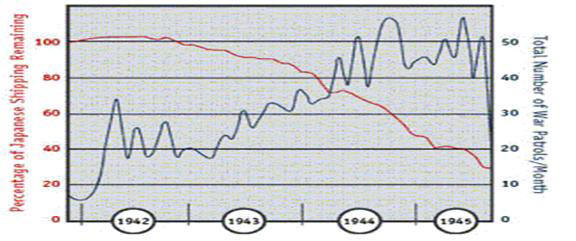

As the number of war patrols from Pearl Harbor, Fremantle, and Brisbane mounted in 1943 and 1944, the percentage of Japanese merchant tonnage remaining afloat dropped. Of note id the peak of U.S. submarine activity in May 1942 in preparation for the Battle of Midway.

Figure ## Patrols versus. Japanese Merchant Shipping tonnage afloat

Missions of modern submarines have grown since the world fought the Axis. New weapons made some missions easier, while other new weapons created missions never dreamt of by Lockwood or Christie. Mahon’s theories no longer have navies large enough to carry out. Instead of sea control, the post-Carter Navy has renamed its role, sea denial. The battleships are all museums or razor bladed. Cruisers are made on destroyer hulls out of beer cans. Congress speaks, and frigates now become destroyers overnight. Yet still, in today’s global economy, with world wide reliance on importation of materials by sea, the primary weapon of sea denial remains the same, the submarine.

During 1,347 days of U.S. involvement in World War II 465 skippers took 263 boats and 16,000 sailors on 1736 war patrols in the Pacific[20]. They attacked 4,114 merchant ships firing 14,748 torpedoes to sink 1,178 merchant ships and 214 ships of the IJN.[21]

[1] It should be noted that JANAC results have known verifiable errors because the Japanese source records JANAC had to use were incomplete. Therefore any tonnage mentioned and attributed to JANAC records is a minimum tonnage and are known to be low. At the same time, VADM Lockwood’s claims for the entire submarine force fielded by the United States Navy in the Pacific totaled out at 10 million tons sunk, 1 million tons more than Japan built.

[2] Michel Thomas Poirier, Commander, U.S.N. “Results of American Pacific Submarine Campaign of World War II”, 30 Dec 1999. Chief of Naval Operations Submarine Warfare Division. (www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/history/ http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/history/pac-campaign.html) 23 January 2005.

[3] Including 8 aircraft carriers, 1 battleship, and 11 cruisers.

[4] Smith, 293.

[5] Blair. 852.

[6] Including all submarines in service in the Atlantic as well as submarines used strictly for training. The number available for Pacific war patrols at any given time was less than 150.

[7] This compares to 781 our of 1159 U-boats and 28,000 crew men killed, 5,000 captured out of 39,000 submariners for the Germans. Japan lost 130 submarines and Italy lost 85 submarines. Blair. 851.

[8] Total force including non-deploying staff and support personnel 50,000 men (less than 2% of the Navy’s manpower). Actual number deploying 16,000 men. Poirier.

[9] Truman. “The Battle of the Atlantic” The History Learning Site

(http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/index.htm http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/atlantic.htm) 29 March 2005. Beach, 21. Gallery, 15.

[10] Beach, 19-20.

[11] Merrigan.

[12] Blair. xv.

[13] Padfield. 384.

[14] Ibid.385.

[15] Ibid.193-194.

[16] Poirier estimates the Japanese were forced to spend the equivalent of $128 billion compared to the cost of $873 for America, a ratio of 42.3:1 in America’s favor.

[17] “The Japanese suffered an important indirect effect of submarine warfare caused by the loss of efficiency due to convoying. The entire merchant marine (including that shipping throughout the empire that was not convoyed) had a loss of efficiency of 8% between January 1942 and January 1944 with a further reduction of 21% by 1945 However, on the critical line between Singapore and Japan, efficiency declined by 45% between May 1943 and May 1944, with further substantial declines later. Not only did Japan have too few ships, but their ships took longer and longer throughout the war to carry badly needed cargoes the same distances.” – Michel Thomas Poirier. “Results of the German and American Submarine Campaigns of World War II.” 20 Oct 1999. (www.chinfo.navy.mil http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/history/wwii-campaign.html) 23 Jan 2005.

[18] Ibid.400.

[19] Merrigan.

[20] Blair. 973.

[21] “Submarine Veterans of World War II, What They Did” (www.submarinevets.com/~subvetsww2/ http://www.submarinevets.com/~subvetsww2/theydid.html) 15 Jan 2005.