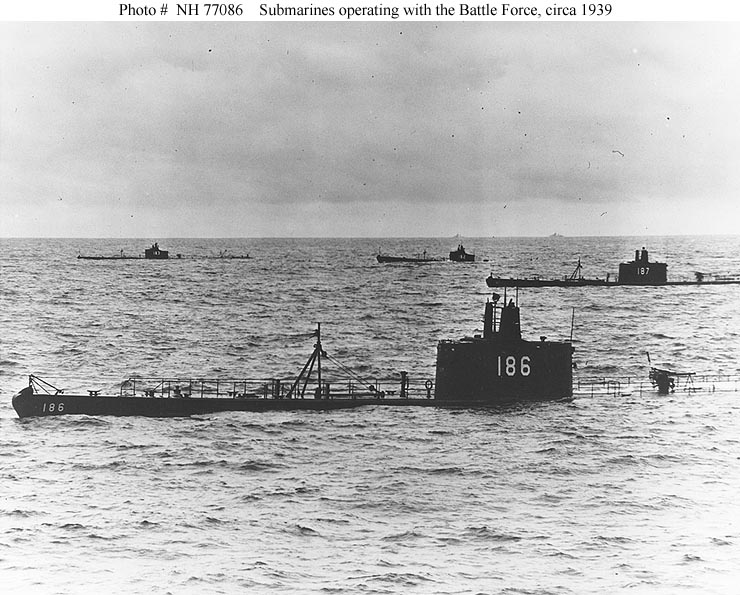

Figure ## USS Stingray (SS-186), foreground operating in formation with other submarines, during Battle Force exercises, circa 1939. The other three submarines are (from left to right): Seal (SS-183); Salmon (SS-182) and Sturgeon (SS-187).

Operations

Submarine operations have their roots in submarine doctrine. As stated before, the “Root Clause” in both the Washington Naval Treaty and London Naval Treaty set the U.S. Navy’s submarine doctrine for the between war years. Submarines would therefore be tasked with attacking surface combatants, vessels of much greater speed and endurance than merchant ships.

The advent of Naval Aviation demonstrated the submarine’s vulnerability to aircraft. Lessons learned from anti-submarine operations (ASW) in World War I showed the submarine’s vulnerability to ASDIC (Allied Submarine Detection Investigation Committee’s abbreviation which was shared with the active developed at the end of the First World War as a result of the committee’s research and actions). Unfortunately, the lessons passed on were of the infallibility of these ASW methods. Therefore, between war fleet exercises (FLEETEX) were structured in a way that any submarine within range of shore based aircraft or 5 miles of an ASDIC equipped escort ship was considered sunk by the FLEETEX umpires. Submarine squadron commanders were harsh with submarine skippers caught/”sunk” during such exercises. The official solution, attack using passive sonar from below 100 feet[1].

Skippers so trained were, on the whole, prone to over cautiousness, but not inaction. December 1941 found Asiatic Fleet boats poorly deployed (fleet boats were sent to stand off ports in Indochina). The inexperienced crews lacked proper training.

“Don’t go out there and win the Congressional Medal of Honor in one day. The submarines are all we have. Your crews are more valuable than anything else. Bring them back.”

- Asiatic Fleet submarine force operations officer.

While this seemed over cautious., it was correct. The surface fleet at Pearl Harbor was in the mud. Soon, the Asiatic surface fleet would be destroyed at the Battle of Java Sea. The Asiatic submarines were the front line. Yet they were not really ready for war. December 1941 found the Asiatic submarine force firing 96 torpedoes in 45 separate attacks. The results were disappointing, only three freighters.[2] This with 23 fleet boats and 6 S-boats.[3] Boats operation out of Pearl Harbor added another 4 ships sunk.[4] The lessons learned that month, the Japanese were good. Their night vision was better than ours and the sonar was effective[5].

The first year of war was hampered by poor doctrine and command, not to mention the torpedoes. Forty of the one hundred thirty five submarine commanders were relieved “for cause”, meaning they could not make the grade needed to win the war[6]. Still, May 1942 brought a sinking rate that the Imperial High Command deemed untenable. The 22 ships ( 107,991 tons) in one month exceeded their predictions of 2.7 million tons spread over three years.[7]

The end of 1942 found 1442 torpedoes fired with only 2,000 produced. RADM Christie used this to speed the production of other facilities such as Keyport, WA. VADM Lockwood and VADM Blandy (BuOrd) were locked in a power struggle over the Mk 6 exploder and the Mk XIV torpedo.[8] Seven submarines had been lost, though not all with all hands. In exchange 186 ships (725,000 tons) of Japanese shipping rested on the bottom.[9]

Unfortunately, the lack of centralized unified command structure split the submarines’ effectiveness. During 1942, GEN Macarthur diverted many submarines to sending ammunition to the beleaguered defenders of Bataan and Corrigedor, as well as rescuing guerillas, nurses, and others deemed critical to the war effort. Other missions in 1942 included coastal defense of the Philippines, a weak attempt to blockade Truk and the Solomons, Magic directed intercepts of IJN warships, commando raids, mine laying reconnaissance, navigation beacon, weather station, and oh by the way, merchant interdiction.[10]

By May 1943, the Arsenal of Democracy showed results. Throughout the Pacific in May, thirteen submarines were lost, but more than fifty had reached the Pacific from American shipyards so far that year. In comparison, the IJN lost 28 submarine and were forced to scrap two but only built 30.[11] June 1943 found the U.S. submarine forces consistently sinking more tonnages per month than the Japanese had facilities to built – 65,000 tons.[12] By September, the sinking in one month were up to 31 ships (125,000 tons). November raised it to 47 ships ( 278,880 tons). The end of December 1943 found the Japanese shipping tonnage available at 5 million tons. This was deemed to be one million tons less than what Japan had to have for survival. Submarine production in America reached six per month.[13]

The year 1943 saw 25 more COs relieved for cause (out of 178). The excess of senior officers at SUBPAC and SUBSOWESPAC were trimmed. Most old time chiefs and officers were ashore now. U.S.NA Class of 1935 (~ 30 years old) came into command of boats. Approximately 350 war patrols fired 3937 torpedoes to sink 335 ships (11.7 torpedoes per ship sunk). In comparison, 1942 sent out roughly the same number of patrols which fired 1442 torpedoes to sink 180 ships (8 torpedoes per ship sunk).[14] VADM Lockwood, RADM Christie, and CAPT Fife were in charge of the submarines. Between them, a sift in tactics finally occurred. Instead of patrolling off harbor, boats were sent to patrol choke points in shipping lanes. Three small wolf packs had been sent out and their results were being analyzed. SJ surface search radar was in work on more boats. Magic was refined and now gave better reports. The Mk XIV finally was ready to go to war. Yet 15 submarines failed to return from patrol.[15]

1944 brought more changes. The combined tonnage sunk by 31 December 1943 totaled out at 2.2 million tons. 1944 would see the end of another 2.7 million tons sunk. Tanker became a priority target.[16] To achieve this, January 1944 started with the sinking of 3 IJN warships and 53 marus.[17] February 1944 saw submarines sinking 250,000 tons (an additional 250,000 tons was sunk by all other U.S.N forces).[18] In May and June 1944, RADM Christie’s boats trimmed IJN ADM Ozawa fleet by 1 light cruiser, 5 destroyers, 1 destroyer escort, 2 frigates, 6 tankers, 4 troopships, and 14 freighters.[19] June also submarines penetrating the ASW minefields to hunt in the South China Sea.[20] With more than a million tons sunk in the first six months of 1944, July accounted for 125,000 tons of warships and 220,000 tons of merchant ships sunk by American submarines.[21]

May 1944 found COMSUBSOWESPAC shifting back to standing patrols off harbors when much of the remaining IJN fleet retreated to Tiwi Tiwi. A standing patrol of several boats kept the fleet from sailing and even prevented training of replacement pilots as the carriers could not leave port safety for carrier landing training.[22] June and July saw the return of wolf packs, this time across the Pacific. Hundreds of Japanese merchant seamen are shipwrecked, with hundreds more afraid to leave port. The shortage of escorts has become critical. Imports, especially oil, fall off drastically. Ship yards cannot produce replacements due to lack of facilities and steel.[23]

On the American side, July 1944 found 140 fleet boats in the Pacific, 100 under COMSUBPAC. The torpedo load out averages 75% Mk XVIIIs and only 25% MkXIVs. The Japanese ASW minefields have been plotted and lack of escorts and raw materials to build more have rendered IJN ASW efforts ineffective.[24]

The summer of 1944 found 8 wolf packs sent by Lockwood stalking shipping in the Luzon Straits. These wolf packs sank 56 ships including one escort aircraft carrier. Nearby SOMSUBSOWESPAC boats (most notably Rasher and Harder) fell on the strays escaping the straits like sharks[25]. In July and August 1944, 653 patrols were sent out Pacific wide with fully half as wolf packs. On 18 August 1944, one of these wolf packs intercepted convoy HI-71 consisting of 20 ships and 5 escorts. When they left, 4 freighters, 1 tanker, 1 troopship, and an escorting light aircraft carrier sat on the bottom. By the end of their patrol, this wolf pack accounted for 13 Japanese ships sunk.[26] By the return of Hydeman’s Hellcats (a nine boat pack) Japanese shipping virtually ceased to exist.[27]

By August 1944, Japan was forced to cut 13 of its shipping routes due to lack of escorts and ships. Shipping of iron ore was cut because the need for bauxite (aluminum ore) for aircraft and lack of bauxite ships remaining afloat.[28]

September 1944 found 700,000 tons of Japanese oil tankers still in service. By December 1944, only 200,000 tons still floated. Japanese resorted to trying to make fuel from potatoes.[29] September and October accounted for an additional 750,000 tons sunk. This was accomplished by 113 war patrols of which 42 returned without sinkings.[30] October brought record submarine losses though. Darter grounded on shoals and had to be abandoned. Seawolf was sunk by U.S. forces. Tang sank due to a circling torpedo of her own. Salmon was scrapped due to damage from depth charges and two others were lost to enemy action[31].

The last half of 1944 found targets running out. The summer and autumn average was 300,000 tons per month. November found Japanese merchant seamen jumping ship rather than sail and tonnage sunk totals diminished.[32] Sadly, the shipping sunk had carried Allied POWs as Japan pulled them back to the Home Islands for labor. More than 4,000 died as a result of sinkings by American submarines.[33]

1944 total damage to the Imperial Japanese Navy included the battleship Kongo, the aircraft carriers, Shokaku, Taiho, Taiyo, Unyo, Jinyo, Shinano, Unryu, as well as 2 heavy cruisers, 7 light cruisers, and more than 70 destroyers and destroyer escorts. U.S. submarine losses totaled at 19 (compared to 7 in 1942 and 15 in 1943) but they rescued 117 airmen. An additional 23 were retired, 3 for severe damage. 35 commanders were relieved U.S.NA Class of 1938 began to command boats. 520 patrols fired 6092 torpedoes to sink 603 ships for 2.7 million tons (an average of 10 torpedoes per ship). 618,000 tons of tankers went to the bottom.[34]

January 1945 found Japan had no oil for ships, or gas for aircraft. The production of weapons, the only thing left in production, fell due to lack of materials.[35] By July 1945, only three of the 123 merchant ships sunk were found outside “home waters.”[36] LCDR Lewellen (Torsk) sank the last two Japanese vessels, two patrol boats, on 14 August 1945. the next day, ADM Nimitz ordered the cessation of offensive operations against the Empire of Japan.[37]

[1] Specter. 482.

[2] Ibid. 130.

[3] Padfield. 184.

[4] Ibid. 192.

[5] Blair. 175

[6] Padfield. 191.

[7] H.P. Willmott. The Second World War in the Far East. (Washington: Smithsonian

Books) 2004. 91.

[8] Blair. 374.

[9] Ibid.333. Padfield. 476.

[10] Blair. 333.

[11] Padfield. 337.

[12] Ibid. 350.

[13] Ibid. 383.

[14] Blair. 523.

[15] Ibid. 480.

[16] Specter. 486.

[17] Padfield. 398.

[18] Blair. 400.

[19] Ibid. 606.

[20] Padfield. 431.

[21] Ibid. 436.

[22] Blair. 606.

[23] Ibid. 661.

[24] Ibid. 668.

[25] Ibid. 696.

[26] Ibid. 667.

[27] Smith. 293.

[28] Wilmott. 165.

[29] Blair. 791.

[30] Padfield. 450.

[31] Ibid. 442.

[32] Ibid.448.

[33] Ibid.745.

[34] Ibid.792.

[35] Blair. 797.

[36] Wilmott. 178.

[37] Smith, 283.