The Submariners[1]

The

Commanders

The

Commanders

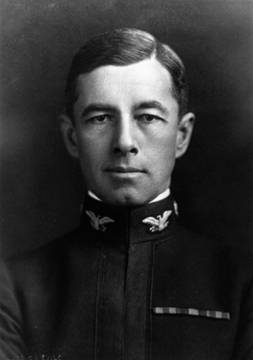

Thomas Hart, born in Davison, MI in June 1877, graduated from the Naval Academy in 1899. Hart attended Naval War College in 1923, the Army War College in 1924, and graduated from both the Armed Forces Staff School and the National War College. During the Spanish-American War, Hart fought in Santiago, Cuba alongside Theodore Roosevelt. Later, LT Hart served as a Division Officer aboard the battleship, U.S.S Missouri (BB-11) and commanded the destroyer, U.S.S Lawrence Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 11 Thomas C. Hart

(DD-8). Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, CDR Hart qualified for Command of Submarines. During World War I, Hart was tasked as commander of submarine operations in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans as Director of Submarines at the Navy Department. While filling that position, Hart chaired the postwar U-Boat Plans Committee. This committee called for the construction of long-range submarines to operate independently in the Pacific. This conference and the ideas spawned there directly led to the World War II fleet submarines that cut Japan’s economic throat.[2] Following World War I, CAPT Hart commanded U.S.S Mississippi (BB-41) and later Submarine Divisions, Battle Fleet, and Submarine Force, U.S. Fleet.[3]

During the 1920s, CAPT Hart lectured at the Naval War College on submarines and their capabilities. The lectures included the following:

“I shall pass over the humane factor of German submarine warfare because they are characteristic of the race. Any nation that attempts commerce destruction by submarines will tend toward certain of the same practices that Germans arrived at; how far it will go depends on its racial characteristics and, very likely, by how hard it is pressed.”[4]

Promoted to Rear Admiral in Sept 1929, RADM Hart was the Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy from 1931 through 1934. From there, RADM Hart assumed the duties as Chair of the Navy’s General Board. As an “old school” submariner, Hat felt the Salmon class submarines were too full of luxury items and gadgets such as air conditioning to prolong the life of the electronics, and the Torpedo Data Computer. RADM Hart advocated the return to smaller less sophisticated submarines with six torpedo tubes (4 forward, 2 aft) of around 800 tons surface displacement.[5]

Thomas Hart, promoted to Vice Admiral in July 1939, became C-in-C, Asiatic Fleet. VADM Hart was at Cavite Naval Base, Philippines when Japan struck on 8 December 1941. Hart’s orders to his command were simple: conduct unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan. Hart’s submarines deployed to counter the expected invasion of the Philippines. The only boats to actually make contact proved Hart’s point regarding submarine size. In the shallow confined coral studded waters of the Philippines, Hart’s S-boats made contact while the newer larger, better equipped fleet boats failed. Unfortunately, the Asiatic Fleet S-boats deployed with Mk XIV torpedoes instead of the older but more reliable Mk Xs. On 26 December 1941, two-days after General Douglas Macarthur left for Australia, VADM Hart left Manila for Soerabaja (Surabaya), Java in the submarine Shark (SS-174). In January 1942, although past retirement age, Admiral Hart assumed the job of Allied Naval Commander, American-British-Dutch-Australian Forces (ABDA). Fighting a desperate defensive withdrawal, Hart was replaced for political reasons, by Admiral Helfrich, RNN (Royal Netherlands Navy )[6]. His command being obliterated in the subsequent naval operations, VADM was detached and retired in the rank of admiral in July 1942[7]. It is only through VADM Hart’s actions that the Asiatic Fleet submarine force survived to retire to Australia and continue the war[8].

Born in Virginia, and raised in Lamar, MO, Charles Lockwood graduated form the Naval Academy in 1912 and spent two years on the battleships Mississippi, and Arkansas[9]. Sent to Manila and Asiatic Station, Lockwood qualified for command in an amazing 90 days. ENS Lockwood assumed command of A-2 (SS-3) in 1914. Taking command of the Submarine Division there in 1917, LT(jg) Lockwood took his

division

to Japan in 1918.[10]

By 1919, he was in Europe where he was assigned duties as executive officer (XO)

of the German UC-97 to bring back across the Atlantic for evaluation.

division

to Japan in 1918.[10]

By 1919, he was in Europe where he was assigned duties as executive officer (XO)

of the German UC-97 to bring back across the Atlantic for evaluation.

From there Lockwood transferred to New London, CT[11] to command G-1.[12] In 1922, LT Lockwood took command of Quiros, a Yangtze gunboat, where he learned to respect his own judgment[13]. Lockwood commanded

Figure 12 ADM Lockwood the submarine V-3 (SS-165, later named Bonita) from 1926 to 1928[14]. 1929 found LT Lockwood in Brazil as part of the United States Naval Mission there.

CDR Lockwood became COMSUBDIV 13 in 1936. From there, Lockwood began his one man campaign for better offensive submarines by bombarding the Navy Department with letters recommending more torpedo tubes in each submarine (6 forward, 4 aft), better engines, radios, and sonar, as well as more speed, improved Torpedo Data Computers (TDC), larger deck guns, longer and thinner periscopes, along with more freshwater capability and more fuel.[15]

This letter campaign resulted in orders in 1937 to assume the “submarine desk” in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO)[16]. There one of his primary duties was as chair of the annual Submarine Officer’s Conference[17]. The May 1938 conference included a spectacular clash between Lockwood and RADM Hart. RADM Hart preferred the smaller submarines of the S-class boats, shorn of any “frills” such as air conditioning or extra fresh water. The results of the 1938 conference were compromises. Hart got 2 small boats, the Mackerel class, while Lockwood and his faction got 6 Tambor class submarines[18]. These new boats were constructed in 1940. 1939 gave Lockwood promotion to CAPT and posting as Chief of Staff, Commander Submarine Forces, U.S. Fleet[19].

CAPT Lockwood was assigned duties as Naval Attaché in London February 1941. There Lockwood observed Royal Navy operations against the German U-boats and examined German tactics and even captured U-boat equipment. Recalled in April 1942, now RADM Lockwood assumed duties as Commander, Submarines, Southwest Pacific (COMSUBSOWESPAC) commanding the remnants of VADM Hart’s Asiatic Fleet submarines. Upon the death of COMSUBPAC, RADM English, ADM Nimitz promoted Lockwood to VADM and gave Lockwood SUBPAC[20].

First as COMSUBSOWESPAC and later as COMSUBPAC, Lockwood listened to his submarine commanders and ordered testing of the Mk XIV torpedo and its Mk 6 magnetic influence exploder. While in Australia, RADM Lockwood commandeered a fishing net and had a submarine fire a series of torpedoes at it, documenting the depth settings. The average result was a depth error of 10 feet too deep. RADM Lockwood sent these test results of to a former U.S.N.A friend now Chief, Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd in Navy terms or frequently called the “Gun Club” by all non-surface types) as well as Naval Torpedo Station (NTS) Newport, Rhode Island. Both NTS and BuOrd denied any problems with the Mk XIV and castigated Lockwood for his improperly documented testing. RADM Lockwood, never one to let his subordinates down, replied by conducted well documented testing with results of a mean error of 11 feet too deep. These results were returned to BuOrd and NTS Newport, with a copy being included in a letter to friend and former submariner RADM Edwards, ADM King’s aide de camp. The results of this exchange will be covered later.

When posted to COMSUBPAC, VADM Lockwood conducted testing on the contact exploder portion of the Mk 6 magnetic influence exploder, again in support of his submarine commanders. When testing reveled engineering problems, Lockwood did not wait on BuOrd or NTS Newport to evaluate the problem. Instead, Lockwood ordered one of his staff, CAPT Momsen[21], to design and issue new reliable contact exploders.

VADM Lockwood, as COMSUBPAC, picked up the nickname from his submarine officers of “Uncle Charlie”. This came from Lockwood’s habit of listening to opinions that differed from what his own experience told him was correct, as well as Lockwood also practice of “downward” loyalty to his subordinates.

Beginning

5 July 1944, VADM Lockwood (COMSUBPAC) and staff met with RADM Christie

(COMSUBSOWESPAC) and staff for what became known as “The Submarine Summit”.

While Lockwood and Christie were at odds over the Mk 6 exploder, their

consummate professionalism refused to allow differences from interfering with

the job at hand. Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 13 CAPT

Christie congratulates LCDR Moore of S-44

Beginning

5 July 1944, VADM Lockwood (COMSUBPAC) and staff met with RADM Christie

(COMSUBSOWESPAC) and staff for what became known as “The Submarine Summit”.

While Lockwood and Christie were at odds over the Mk 6 exploder, their

consummate professionalism refused to allow differences from interfering with

the job at hand. Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 13 CAPT

Christie congratulates LCDR Moore of S-44

Together, Lockwood, Christie and staffs worked out many problems such as Area of Operations Responsibility (AOR) boundaries, spare parts supplies, cycling of Christie’s submarines through Lockwood’s repair facilities, and sharing of technical experts[22].

During Lockwood’s tenure as COMSUBSOWESPAC and COMSUBPAC, Lockwood maintained correspondence with CAPT Ralph Christie (later RADM) in charge of the submarine forces in Brisbane and later Fremantle, Australia (as Lockwood’s replacement at COMSUBSOWESPAC). Christie’s impact on the Pacific submarine campaign began shortly after his 1915 graduation from the U.S.N.A. Selected to obtain a masters degree in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Christie focused his master’s research on the development of a magnetic exploder for torpedoes[23]. Throughout the development of the magnetic exploder, Christie was involved as project officer and later in BuOrd as head of the Torpedo Section[24]. In 1937, Christie predicted a 1942 shortage of torpedoes amounting to 2,425 torpedoes – without the war[25]. During the 1938 Submarine Officer’s Conference, Christie strongly advocated the Tambor class submarine.[26]

During his tenure as COMSUBSOWESPAC, RADM Christie became the first Force Commander and first naval flag officer to make a submarine war patrol. On his first patrol, on the Bowfin, Christie performed duties as a junior watch officer when ever possible to relieve those who would be needed at night for attacks to get more sleep. On this patrol, Christie, as OOD on the bridge during a night surface attack, witnessed LCDR Griffith sink a vessel later not credited by JANAC[27]. RADM Christie later attached himself for another war patrol without notifying his superior, VADM Kinkaid (COM 7th FLEET) of his absence. VADM Kinkaid later used this as an excuse to replace the abrasive Christie with CAPT Fife in December 1944.[28] RADM Christie was transferred to command Bremerton Naval Shipyard and retired from there following the war.

By the end of 1944, RADM Christie had great reason to note the world wide nature of the war in his AOR. In October of that year, Christie noted in his journal of greeting “A Dutch sailor in a British submarine under American Task Force command returning to an Australian port after sinking a German submarine in waters the Japanese thought were theirs.” RADM Christie rewarded H.A.W. Goorsens R.N.N with, what else, a bottle of Canadian Club whiskey.[29]

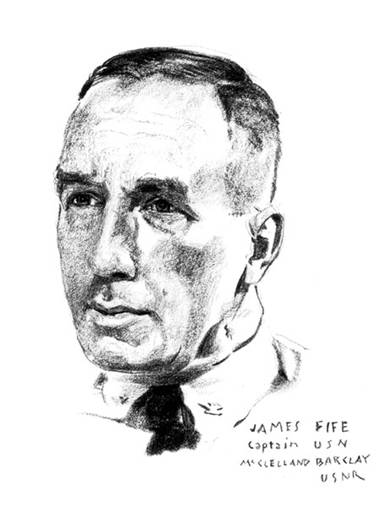

James

Fife was another staff officer and force commander of submarines fighting

Japan. The beginning of war found CAPT Fife

James

Fife was another staff officer and force commander of submarines fighting

Japan. The beginning of war found CAPT Fife

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 14 CAPT James Fife by McClelland Barclay, 1942

acting as Chief of Staff for CAPT Wilkes COMSUBAS (Commander, Submarines, Asiatic Fleet). After the submarine force retreated from the Philippines and regrouped in Australia[30], RADM Lockwood made CAPT Fife COMSUBRON (Commander, Submarine Squadron) Two[31]. Later, CAPT Fife interacted with both VADM Lockwood and RADM Christie as GEN Macarthur’s submarine liaison officer. The January 1943 shuffle of force commanders brought CAPT Fife to command at Brisbane[32]. The subsequent loss of three of the five boats that left Brisbane to patrol in February 1943 led to an investigation of Fife. Following the Solomons Island campaign, Fife’s force was reduced to one squadron[33].

Fife’s response was to create a forward base for his squadron at Milne Bay, New Guinea cutting 1200 miles off the fuel bill. Between July and December of 1943, CAPT Fife’s 8 boats sank at least 29 ships in 33 patrols. During the same time, RADM Christie’s 22 boats from Fremantle sank 50 Japanese vessels. In early 1944, the war pushed Japan’s fleet west of Brisbane’s AOR. The boats were transferred to Brisbane and Christie and Fife transferred to Washington for staff duty. December 1944 found RADM Fife back in the Pacific now as COMSUBSOWESPAC, commanding 7th Fleet submarines[34].

Many of the critical submarine personnel filled staff positions for most of the war and missed much of the recognition. CAPT Henry Anthony, US Coast Guard, was recalled from retirement to command the cryptological section at Hypo (later named Fleet Radio Unit Pacific or FRUPAC) responsible for breaking the low level “maru codes” that daily reported merchant ship positions, course, speed, and destination[35]. CAPT Dick Voge (SUBPAC Operations officer) used the take from the broken maru codes to position submarines on patrol to intercept[36]. Voge also worked out the rotation of boats to overhaul facilities such as Mare Island, CA and Pearl Harbor, HI. Shortages of submarines caused by the H.O.R. engine fiasco created a shortage of submarines on patrol so than for a period in 1943, Voge had more intelligence information than boats on patrol to make use of it[37]. War’s end found Voge a rear admiral. Voge’s greatest work began in August 1945 as he compiled all the operational data from patrol reports, logs, and records for Theodore Roscoe, writer of States Submarine Operations in World War II arguably the definitive source of information on submarine operations in the Pacific during World War II.

Charles

“Swede Momsen, U.S.N.A Class of 1919, completed submarine school in 1922.

Involved in the salvage of S-4, Momsen discovered that six sailors survived

three days in the torpedo room after S-4 sank, but died with no way out. As a

result of this, Momsen developed the “Momsen lung”, an oxygen rebreather while

stationed with Submarine Safety Test Unit onboard the

Charles

“Swede Momsen, U.S.N.A Class of 1919, completed submarine school in 1922.

Involved in the salvage of S-4, Momsen discovered that six sailors survived

three days in the torpedo room after S-4 sank, but died with no way out. As a

result of this, Momsen developed the “Momsen lung”, an oxygen rebreather while

stationed with Submarine Safety Test Unit onboard the

salvaged S-4. Often used to fight fires or escape from battery fumes, many of the crew Figure 15 Charles "Swede" Momsen

of Tang used the Momsen lung to survive the smoke and fumes following Tang being sunk by a circling torpedo. Thirteen of the submerged crew were known to leave the boat using their Momsen lungs.

Momsen pioneered in developing helium-oxygen (heliox) for deep diving. When the Squalus sank, command of the rescue effort went to “Swede” Momsen because of his deep diving expertise and salvage experience. Using the McCann Rescue Chamber (developed by Momsen and perfected by Allan McCann after Momsen transferred), 33 crewmen were rescued from 243 feet down. Momsen also supervised the salvage of Squalus.

During World War II, CDR Momsen held the positions of COMSUBRON Two and COMSUBRON Four. While in these positions at Pearl Harbor under VADM Lockwood, Momsen inherited several technical problems. Among other things, Momsen redesigned the contact exploder for the Mk XIV torpedo’s Mk 6 exploder. Momsen, as commander of the first wolf pack, developed a two letter code to streamline communications[38] between submarines in the wolf pack[39]. When Momsen noted the difficulty in communicating with the wolf pack mates, he later developed what became known as “Gertrude”, a low power low frequency underwater communications. Momsen also devised a way to sent simple Morse signals with the periscope mounted ST radar (of course using his two letter code groups). These signals were received by the other radar sets of the boats in the wolf pack. For his heroism commanding the first wolf pack Momsen received a Navy Cross. His other side work with technical issues accorded him the Legion of Merit[40].

The Captains

The submarine commander was the personification of the submarine and her crew. Only he could see outside during most attacks. Only he made decisions. On submarines, the will of the CO was more evident in the actions of the crew than in any other type naval vessel[41].

All navies had a small number of “aces” who performed well above the average. The common factors were aggressiveness, determination, calmness under pressure, and painstaking attention to crew training[42]. The United States Navy began the war with submarine commanders in their upper 30s as LTs or LCDRs (S-boats and Fleet boats respectively). These COs were the product of the 1930s Fleet Exercises (FLTEX) which required the submarines to attack by sonar from depths below 100 feet. As a rule, this generation of CO was overly cautious, trained to believe ASDIC and aircraft were infallible.

By 1945, the COs were predominantly in their late 20s to early 30s. These aggressive commanders were responsible for the devastating campaign which severed Japan from overseas material and supplies[43]. Many satisfactory peacetime officers proved lacking in qualities of successful wartime submarine commanders[44]. The 1920s United States Naval Academy and Navy promotion system produced officers who “burned out” by the time they assumed command. They tended to become inflexible and strict disciplinarians[45].

December 1941 found submarine wardrooms primarily composed of U.S.N.A graduates. All commands went to Naval Academy graduates. The prewar Naval Academy taught midshipmen to emphasize the reputation of the service and the officer over curriculum and knowledge. The molding of proper character in these gentlemen received higher priority than intellect[46].

The typical wartime submarine commander was hand picked, and highly qualified. Due to the small crew sizes, officers could not be “carried” by subordinates and crew. Success, even survival, of the entire crew depended on the judgment, skill, and nerve of the commanding officer. The clash between prewar training and these wartime requirements ruined the career of many an officer. In 1942 almost 30% of submarine commanders were relieved for cause, that is failure to produce results. During 1943 and 1944, VADM Lockwood relieved 14% of submarine commanders[47]. Due to the abundance of qualified officers available by that time, VADM Lockwood relieved any commander who returned from war patrol twice in a row with no ships sunk. Several gained second chances at command following superior performance in SUBPAC staff positions.

While some of the submarine commanders in December 1941 lacked the aggressiveness needed for war time command, some aggressive CO sought out anything Japanese to sink. LT Wreford C. “Moon” Chapple (S-38) refused to let small barriers such as IJN destroyers patrolling the entrance to Lingayen Gulf, an obsolete submarine, or coral reefs deter him. With the entrance blocked, Chapple and S-38 found a way through and over the reefs at high tide during the night. Immediately following the first failed attack inside Lingayen Gulf, Chapple deduced the Mk XIV torpedoes were running too deep. Resetting the depths, S-38 attacked again[48]. Though severely depth charged in the shallow waters of the gulf, Chapple and S-38 continued to attack at every opportunity gaining a confirmed sinking of 1 ship of 5445 tons[49]. This one boat war ended only when S-38 received serious. battery damage and a recall order from COMSUBAS[50].

LCDR

Nicholas Lucker (S-40) also got his crew and boat into the landing area by

sneaking over a reef. Obtaining firing position without being detected, Lucker

fired four torpedoes. All failed to explode. In return, S-40 received a

damaging depth charging by the escorts and limped away for repairs[51].

LCDR

Nicholas Lucker (S-40) also got his crew and boat into the landing area by

sneaking over a reef. Obtaining firing position without being detected, Lucker

fired four torpedoes. All failed to explode. In return, S-40 received a

damaging depth charging by the escorts and limped away for repairs[51].

1943 displayed many dedicated submariners. In January 1943, LCDR Howard Gilmore (Growler) conducted a surface attack on an armed trawler. When the Japanese vessel’s guns raked the bridge of Growler, many of the lookouts

and bridge crew were wounded or killed. With the dead keeping him company, Gilmore, severely wounded himself and unable to get below on his own, Figure 16 CDR Gilmore hollered down the open hatch, “Take ‘er down!” Then Gilmore slammed the

hatch

closed from the outside and dogged it down. Damage to Growler caused the

XO to resurface very shortly, but when the gun crews scrabbled out to take the

trawler under fire again, the trawler was already sunk and the dead along with

LCDR Gilmore were already washed away. For his actions, LCDR Gilmore

posthumously received the Medal of Honor[52].

hatch

closed from the outside and dogged it down. Damage to Growler caused the

XO to resurface very shortly, but when the gun crews scrabbled out to take the

trawler under fire again, the trawler was already sunk and the dead along with

LCDR Gilmore were already washed away. For his actions, LCDR Gilmore

posthumously received the Medal of Honor[52].

The end of 1942 found LCDR Dudley “Mush” Morton the new commander of Wahoo. Figure 17 LCDR Morton

Morton

chose to retain the executive officer, LT Dick O’Kane. Morton chose to differ

in his attack tactics. Instead of the CO using the periscope, Morton believed

in placing the XO on the periscope.[53]

LCDR Morton felt this freed the CO to analyze the situation better. Using this

practice, in four war patrols, Morton and Wahoo sank 15 ships. O’Kane

detached following that patrol to take command of Tang. In October 1943,

on his fifth patrol, Morton and Wahoo did not return. Japanese

Morton

chose to retain the executive officer, LT Dick O’Kane. Morton chose to differ

in his attack tactics. Instead of the CO using the periscope, Morton believed

in placing the XO on the periscope.[53]

LCDR Morton felt this freed the CO to analyze the situation better. Using this

practice, in four war patrols, Morton and Wahoo sank 15 ships. O’Kane

detached following that patrol to take command of Tang. In October 1943,

on his fifth patrol, Morton and Wahoo did not return. Japanese

Figure 18 LT O’Kane on periscope records after the war proved Morton had sunk another four ships in the Sea of Japan. This gave Morton a total of nineteen ships sunk, good enough for second place for the war in the Pacific. LCDR Dudley Morton earned four Navy Crosses for his actions, one from each war patrol he returned from[54].

Newly

promoted LCDR Dick O’Kane took command of the newly constructed Balao

class boat Tang. January 1944 found O’Kane and Tang leaving on

their first war patrol together. Following Morton’s practice of placing the XO

on the periscope, O’Kane and Tang sank their first ship 17 February

1944. 22 February found Tang sinking two more with two more going down

from Tang’s ministrations two nights later for a total for

Newly

promoted LCDR Dick O’Kane took command of the newly constructed Balao

class boat Tang. January 1944 found O’Kane and Tang leaving on

their first war patrol together. Following Morton’s practice of placing the XO

on the periscope, O’Kane and Tang sank their first ship 17 February

1944. 22 February found Tang sinking two more with two more going down

from Tang’s ministrations two nights later for a total for

the first war patrol of five confirmed sinkings Figure 18 LT Dick O'Kane

(21,400 tons)[55]. O’Kane and Tang, together for Tang’s entire life, were credited by JANAC at war’s end with twenty six kills, the most for any single commander. Among Tang/O’Kane’s other deeds comes the second war patrol resulting in the rescue of 22 downed airmen on 30 April 1944 during the Navy’s Truk Raid[56]. Third and fourth war patrols tonnage sunk totaled at 50,600. O’Kane led the crew of Tang on a fifth war patrol, this time in the South China Sea. After a fruitful patrol, O’Kane directed Tang after a stray survivor of a convoy they had ambushed on 24 October 1944. Firing the last two torpedoes onboard, the first struck the freighter but the second circled back and sank Tang. O’Kane and four others made off the bridge or out of the conning tower.

The

sinking submarine did not immediately kill the rest of the crew. Controlled

flooding of ballast tanks allowed Tang to settle on the bottom on an even

keel. With fumes filling many compartments from battery damage, the surviving

crew gathered forward, using Momsen lungs to breath in the toxic

atmosphere. Thirteen men exited the escape trunk again using Momsen lungs.

Eleven reached the

The

sinking submarine did not immediately kill the rest of the crew. Controlled

flooding of ballast tanks allowed Tang to settle on the bottom on an even

keel. With fumes filling many compartments from battery damage, the surviving

crew gathered forward, using Momsen lungs to breath in the toxic

atmosphere. Thirteen men exited the escape trunk again using Momsen lungs.

Eleven reached the

Figure 19 Tang and her 22 rescued airmen surface. Eight joined up with O’Kane and the other survivors[57]. The next morning found the five bridge survivors and four of the escapees alive. “Rescued” by a Japanese destroyer, they finished the war in a POW camp. Treatment for the submariners was harsh. O’Kane weighed only 88 pound when rescued in September 1945. With twenty four JANAC confirmed sinkings (for first place) Richard O’Kane received the Medal of Honor for his exploits with Tang[58].

CDR John P. Cromwell (promoted to CAPT during

patrol), a submarine division commander, sailed aboard Sculpin in

November 1943 to command a three boat wolf pack. On 18 November, Sculpin

received a severe depth charging. The next day, during yet another extreme

depth charge attack, damage forced Sculpin to surface to fight it out

with

the IJN destroyer. The IJN vessel mortally damaged Sculpin. On the

bridge Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 20 CDR Cromwell

with a chance to dive over sink board, CAPT Cromwell chose to go below and with

the boat rather than be captured and possibly reveal what he knew of American

breaking of Japanese codes as well as his knowledge of major operations soon to

come in the Gilbert Islands. Twelve crew men also chose to ride Sculpin

down[59].

Cromwell received the Medal of Honor posthumously for this[60].

with

the IJN destroyer. The IJN vessel mortally damaged Sculpin. On the

bridge Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 20 CDR Cromwell

with a chance to dive over sink board, CAPT Cromwell chose to go below and with

the boat rather than be captured and possibly reveal what he knew of American

breaking of Japanese codes as well as his knowledge of major operations soon to

come in the Gilbert Islands. Twelve crew men also chose to ride Sculpin

down[59].

Cromwell received the Medal of Honor posthumously for this[60].

By 1944, new examples of the ideal submarine commander existed. Men like “Mush” Morton, Dick O’Kane, and Sam Dealey[61] commanded boats (and crews) like Wahoo, Tang, and Harder[62].

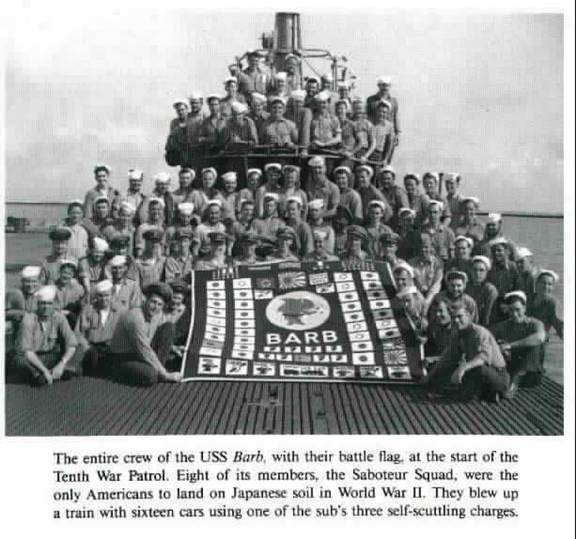

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 21 Barb and her battle flag signifying sinking of a 16 car train

Eugene Fluckey, U.S.N.A Class of 1935, started the war in the wardroom onboard Bonita. In April 1944, after five war patrols, LCDR Fluckey assumed command of Barb. Fluckey sank the record tonnage for a single skipper with the fifteen ships Barb sank under his command. When shipping dried up due to success of the submarine forces, Fluckey sent a party ashore to destroy a rail bridge. Destruction of the bridge also earned Fluckey and Barb credit for sinking a sixteen car train. For heroism during the ship’s eighth, ninth, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth war patrols, LCDR Fluckey earned four Navy Crosses and the Congressional Medal of Honor[63]. Barb, Fluckey, and her crew earned the Presidential Unit Citation and Navy Unit Commendation for these same patrols[64].

Another

new aggressive commander to assume command in April 1944 was Manning Kimmel.

The son of VADM Kimmel of Pearl Harbor infamy and nephew of 7th Fleet

commander ADM Kinkaid, LCDR Kimmel took Rabalo on two war patrols.

Damaged by depth charges early in the patrol, Manning Kimmel stayed on station

patrolling in a boat damaged beyond the crew’s ability to repair. Aggressively

pursuing the Japanese, Kimmel sank a 7,500 ton freighter that patrol[65].

Another

new aggressive commander to assume command in April 1944 was Manning Kimmel.

The son of VADM Kimmel of Pearl Harbor infamy and nephew of 7th Fleet

commander ADM Kinkaid, LCDR Kimmel took Rabalo on two war patrols.

Damaged by depth charges early in the patrol, Manning Kimmel stayed on station

patrolling in a boat damaged beyond the crew’s ability to repair. Aggressively

pursuing the Japanese, Kimmel sank a 7,500 ton freighter that patrol[65].

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 22 LCDR Manning Kimmel On the second patrol with Rabalo

in

June-July 1945, Kimmel struck a mine in Balabac Strait while returning to

Fremantle. Kimmel and the bridge crew survived and swam ashore. Captured by

Japanese troops on Palawan, Kimmel and his crew mates suffered great abuse at

the hands of the Japanese Army. Following a successful U.S. air raid on

Palawan, Philipino guerillas witnessed the Japanese pushing Kimmel and his

fellow Rabalo survivors into a ditch. Once in the ditch, Japanese doused

them liberally with gasoline and set them on fire. Upon learning of this, RADM

Christie quickly yanked younger brother Thomas Kimmel from the boat he XO’d and

ignoring all pleas, shipped the remaining young Kimmel to shore duty in

accordance with orders from VADM Kinkaid, ADM King, the Sullivan Brothers’ Act

and the Naval Academy Protection Association (NAPA)[66].

in

June-July 1945, Kimmel struck a mine in Balabac Strait while returning to

Fremantle. Kimmel and the bridge crew survived and swam ashore. Captured by

Japanese troops on Palawan, Kimmel and his crew mates suffered great abuse at

the hands of the Japanese Army. Following a successful U.S. air raid on

Palawan, Philipino guerillas witnessed the Japanese pushing Kimmel and his

fellow Rabalo survivors into a ditch. Once in the ditch, Japanese doused

them liberally with gasoline and set them on fire. Upon learning of this, RADM

Christie quickly yanked younger brother Thomas Kimmel from the boat he XO’d and

ignoring all pleas, shipped the remaining young Kimmel to shore duty in

accordance with orders from VADM Kinkaid, ADM King, the Sullivan Brothers’ Act

and the Naval Academy Protection Association (NAPA)[66].

LCDR Bernard Clarey (Pintado) performed a singular feet in August 1944. Clarey sank Tonan Maru II. While most would not consider this feat to unique, it must be noted that Clarey, as XO of Amberjack, conducted the attack on 10 October 1943 inside Kavieng Harbor on Tonan Maru II[67]. Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 23 RADM Clarey Both sinkings were verified by JANAC after the war[68].

September 1944 found LCDR Frank Acker (Pomfret)

paralyzed

by a back injury received when Pomfret was tossed around by a typhoon.

Commanding the boat while lying in bed, Acker had his XO, LT

paralyzed

by a back injury received when Pomfret was tossed around by a typhoon.

Commanding the boat while lying in bed, Acker had his XO, LT

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 24 U.S.S Pomfret Clarke

man the periscope. By 30 September 1944, Acker’s severe pain and subsequent

heavy medicated state led to him officially turning command over to

LT Clarke. Clarke reported the change of

command and Acker’s condition demanding a recall to the forward base at Guam so

Acker could receive immediate proper medical care. VADM Lockwood quickly

replied for Clarke to bring Acker in. On the way to Guam, Clarke sited a

Japanese convoy and set up the attack. As the boat moved to proper position,

Acker surprised everyone by dragging himself to the conning tower and on to the

periscope by using his arms only. Clarke conceded command for this attack.

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 25 LCDR George Grider 2nd from right

Acker hung onto the periscope handles and was raised and lowered with it.

The quartermaster helped turn the periscope for Acker. In his last attack as a

submarine commander, Acker fired at two freighters. JANAC’s post war combing of

Japanese records confirmed the sinking of Touyama Maru (6962 tons)[69].

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 24 U.S.S Pomfret Clarke

man the periscope. By 30 September 1944, Acker’s severe pain and subsequent

heavy medicated state led to him officially turning command over to

LT Clarke. Clarke reported the change of

command and Acker’s condition demanding a recall to the forward base at Guam so

Acker could receive immediate proper medical care. VADM Lockwood quickly

replied for Clarke to bring Acker in. On the way to Guam, Clarke sited a

Japanese convoy and set up the attack. As the boat moved to proper position,

Acker surprised everyone by dragging himself to the conning tower and on to the

periscope by using his arms only. Clarke conceded command for this attack.

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 25 LCDR George Grider 2nd from right

Acker hung onto the periscope handles and was raised and lowered with it.

The quartermaster helped turn the periscope for Acker. In his last attack as a

submarine commander, Acker fired at two freighters. JANAC’s post war combing of

Japanese records confirmed the sinking of Touyama Maru (6962 tons)[69].

In December 1944, George Grider (Flasher[70])

sank two IJN DDs (Kishinami and Iwanami, 2100 ton apiece) and the

tanker Hakko Maru (10,000 tons) in his first attack as CO, using 11

torpedoes. Later that same month, Grider sank three out of five tankers in one

convoy (Omurosan Maru 9200 tons, Otowasan Maru 9200 tons, and

Arita Maru 10,238 tons)[71].

In December 1944, George Grider (Flasher[70])

sank two IJN DDs (Kishinami and Iwanami, 2100 ton apiece) and the

tanker Hakko Maru (10,000 tons) in his first attack as CO, using 11

torpedoes. Later that same month, Grider sank three out of five tankers in one

convoy (Omurosan Maru 9200 tons, Otowasan Maru 9200 tons, and

Arita Maru 10,238 tons)[71].

LCDR George Street (Tirante) on two patrols in March and May 1945 sank eight ships according to JANAC. Ned Beach, then Street’s XO, witnessed several from the bridge that JANAC record searches could not account for. Beach and Street stick by their claim of 11 ships in excess of 35,000 tons[72]. Beach Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 26 CDR George Street also notes that according to Japanese records, Japan sank 468 American submarines. The end of 1945 saw the commissioning of the 489th submarine built for the U. S. Navy. Japan claimed to have sunk more than the U.S. Navy had afloat anywhere during the war[73].

Unfortunately, some submariners were pushed too far. LCDR Merrill (Batfish) received the Silver Star for his first patrol as CO and was relieved of command (ala

Caine Mutiny) following his third

war patrol[74].  LCDR

Jordan (Finback) sited the retreating IJN fleet. The speed and zigzag course of

the fleet kept Jordan from attacking and a serious. working over by the

escorting destroyers kept Jordan from reporting. Upon return, Jordan requested

to be relieved. COMSUBPAC quietly granted his request. Great commanders like

“Mush” Morton and Sam Dealey may also have been pushed too far. Following

the loss of each of these aggressive commanders, charges were whispered that

each had been coerced into going back out one more

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 27 CAPT Ned Beach time when each

had expressed the need for a break[75].

LCDR

Jordan (Finback) sited the retreating IJN fleet. The speed and zigzag course of

the fleet kept Jordan from attacking and a serious. working over by the

escorting destroyers kept Jordan from reporting. Upon return, Jordan requested

to be relieved. COMSUBPAC quietly granted his request. Great commanders like

“Mush” Morton and Sam Dealey may also have been pushed too far. Following

the loss of each of these aggressive commanders, charges were whispered that

each had been coerced into going back out one more

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 27 CAPT Ned Beach time when each

had expressed the need for a break[75].

Reserve officers were discriminated against by the UNSA graduates in command of the different submarine forces[76]. In 1944, only three were given command of boats[77] where as the vast majority of submarine wardrooms consisted of reserve officers through out the war[78]. VADM Lockwood’s refusal to allow reserve officers command resulted in the promotion of junior and less experienced academy graduates to command[79]. In 1945 COMSUBPAC and COMSUBSOWESPAC both gave two reserve officers each command of boats for a total of seven reserve officers having command out of 465 commanding officers in Pacific submarines[80].

Pre-war submarine enlisted crewmen tended to be older long service personnel, primarily due to the Depression. The 1930s reenlistment rate was 90%. This created a problem as 17 of every 18 men trying to enlist were turned away due to lack of billets[81]. In comparison, the prewar Army was much poorer quality. Fully 75% failed to finish high school (41% never went to high school) and illiteracy was common[82]. The quality of enlisted submarine crewmen in World War II was such that almost 50% of submarine qualified enlisted crewmen had been commissioned by war’s end[83].

Volunteers composed the majority of submarine crews that fought the war Some officers and special ratings were volunteered without their agreement, but they were the exception. Crewmen, officer and enlisted, focused training on team work. The small crew sizes made each individual important to the whole effort[85]. Slackers had no where to hide. Discipline was maintained by self-respect and competence over threats or use of the “Rocks and Shoals”. The hardships of submarine duty created special bonds among crews and high morale. The typical submariner was a non-conformist who was very confident but not a braggart[86].

Figure ##. The First US Navy submariners. In the center of the

picture is Lt. Harry H. Caldwell, Commanding Officer. Starting at the

lower left of the picture and going clockwise are; William H. Reader,

Chief Gunner's mate; Augustus Gumpert, Gunner's mate; Harry Wahab,

Gunner's mate First Class; O. Swanson, Gunner's mate First Class; Owen Hill,

Gunner; W. Hall, Electrician's mate Second Class; Arthur Callahan,

Gunner's mate Second Class; Barnett Bowie, Chief Machinist's Mate.

The Heel

The one man responsible for the most United States Navy submarines sunk was Congressman Andrew Jackson May of the House Military Affairs Committee. When briefed in 1943 that Japanese escorts were typically setting their depth charges at 100 feet since they were unaware that U.S. submarines could go deeper than that, Congressman May promptly held a news conference in June of 1943 and told of the Japanese errors and the true depths our submarines could attain. Within one month, Japanese depth charges had been set much deeper. After the war, VADM Lockwood equated this single act to a loss of ten U.S.N. submarines.[87]

[1] Of the World War II submariners, the one with the most impact on the future U.S. submarine force never commanded a submarine. CAPT George Hyman Rickover served onboard S-48 reputed to be the worst of the S-boats. Rising to the position of XO, Rickover was deemed not qualified for command during the war and crossed over to Engineering Duty Officer. Father of the Nuclear Submarine, Rickover personally selected all officers to serve on nuclear powered submarines, even after his retirement. Only death got Rickover's fingers out of the nuclear submarine pie. (Blair. 856)

[2] Submarine Warfare Division “Thomas C. Hart” Submarine Pioneers (www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/history http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/history/pioneers4.html#Thomas%20C.%20Hart) 25 April 2005

[3] Smith. 47.

[4] Ronald R. Specter Eagle Against the Sun. (New York: The Free Press) 1985. 478.

[5] Smith. 47.

[6] Jan Visser. “Admiral Thomas Charles Hart” Dutch East Indies 1941-1942 Website (www.geocities.com/dutcheastindies/ http://www.geocities.com/dutcheastindies/hart.html) 11 April 2005.

[7] Though technically retired, Hart was immediately recalled and served admirably on the Navy’s General Board and later conducted an in-depth inquiry into the Pearl Harbor attack. Following his re-retirement at the war’s end, Hart briefly served as a senator from Connecticut.

[8] Naval History Center. “Thomas C. Hart” (www.history.navy.mil http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/t4/thomas_c_hart.htm) 2 March 2005.

[9] Smith. 38.

[10] Ibid. 38.

[11] Commanded by one CAPT Ernest J. King following his qualification as submariner.

[12] Ibid. 38.

[13] Smith. 41.

[14] Blair. 45.

[15] Ibid. 45.

[16] Smith. 41.

[17] The Submarine Officer’s Conference provided feedback from the fleet and in essence decided the future of submarine design.

[18] The Tambor Class was probably the most effective submarines of the war.

[19] Ibid. 41.

[20] Ibid. 43.

[21] Momsen, while not a designated Engineering Officer, had already built quite a reputation as a successful engineer designing the Momsen lung, a oxygen rebreather designed to assist submariners to escape from sunken submarines.

[22] Blair. 646.

[23] Ibid. 33.

[24] Ibid. 45.

[25] Ibid. 48.

[26] Ibid. 48.

[27] Ibid. 585.

[28] Ibid. 789.

[29] Ibid. 718.

[30] Ibid. 194.

[31] Edward C. Whitman. “Rising to Victory: The Pacific Submarine Strategy of World War II: Part I”, Undersea Warfare, Vol 3, Number 3, Spring 2001 (www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/U.S.w/issue_12/contents.html http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/U.S.w/issue_12/rising.html) 11 April 2005.

[32] Padfield. 338.

[33] Edward C. Whitman. “Rising to Victory: The Pacific Submarine Strategy of World War

II Part II”, Undersea Warfare, Vol 3, Number 4, Summer 2001 (www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/U.S.w/issue_12/contents.html http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/U.S.w/issue_12/rising.html) 11 April 2005.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Padfield. 386.

[36] Ibid. 391.

[37] Blair. 373.

[38] Smith, 65.

[39] German wolf packs had to radio back to central headquarters to get information to other wolf pack members.

[40] “Vice Admiral Charles B. Momsen” FleetSubmarine.com (www.fleetsubmarine.com http://www.fleetsubmarine.com/momsen.html) 23 January 2005.

[41] Beach. 5.

[42] Padfield. 14.

[43] Ibid. 15.

[44] Specter. 130.

[45] Ibid. 49.

[46] Ibid. 18.

[47] Ibid. 481.

[48] Padfield. 187-188.

[49] “S-38, SS 143” FleetSubmarine.com (www.fleetsubmarine.com http://www.fleetsubmarine.com/ss-143.html) 23 January 2005.

[50] Padfield. 187-188.

[51] Ibid. 190.

[52] Ibid. 303-304.

[53] Smith. 73.

[54] Padfield. 344.

[55] Ibid. 399.

[56] Hiram Cassedy’s Tigrone was the only boat to beat Tang’s rescue number. In May 1945, over the entire patrol, Tigrone rescued 31 downed airmen. Blair. 582.

[57] Ibid. 44.

[58] “Rear Admiral Richard O’Kane” FleetSubmarine.com (www.fleetsubmarine.com http://www.fleetsubmarine.com/okane.html) 23 January 2005.

[59] Padfield. 392-394.

[60] In a sad irony of history, the 42 survivors of Sculpin were not out of danger yet. Taken onboard the Japanese destroyer, the Japanese tossed a severely wounded American overboard rather than treat his wounds. The three officers and thirty eight enlisted men received ten days of severe questioning at the IJN base on Truk. From there, 21 were placed on the carrier Chuyo, with the other 20 placed on a sister ship, both headed for Japan. On 31 December 1943, Chuyo took several torpedoes from Sculpin’s sister ship, Sailfish. All twenty one Americans onboard died. The saddest portion of this side note was in 1939, off Portsmouth, NH, Sculpin had found Squalus after a failed induction valve sank Squalus. Sculpin had been able to call in rescue efforts and thirty three Squalus. crew were saved. Squalus was salvaged and recommissioned. Under naval tradition, the boat was renamed when recommissioned. The new name for this boat saved by Sculpin – Sailfish. Howard, “U.S.S Sculpin SS 191” Submarine Veterans of World War II (www.submarinevets.com/~subvetsww2/ http://www.submarinevets.com/~subvetsww2/191.html) 15 April 2005. Padfield. 394-396.

[61] The single rescue made by Sam Dealey and the crew of Harder of an airman actually on shore of a Japanese controlled island is told by the rescued, John R. Galvin in Joe Foss’s book Top Guns. Galvin finished out the patrol with Harder qualifying as a watch officer and proudly wearing his dolphins earned there.

[62] Beach. 253.

[63] He is also entitled to wear the ribbons of the Presidential Unit Citation and Navy Unit Commendation awarded to the Barb for those actions.

[64] “Rear Admiral Eugene Fluckey” FleetSubmarine.com (www.fleetsubmarine.com http://www.fleetsubmarine.com/fluckey.html) 23 January 2005.

[65] Blair. 599.

[66] Ibid. 661.

[67] Tonan Maru II was sunk in Kavieng Harbor and later salvaged and repaired.

[68] Ibid. 673.

[69] Ibid. 704.

[70] Flasher would eventually sink 100,231 tons of Japanese shipping.

[71] Ibid. 771.

[72] Beach. 152.

[73] Ibid. 65.

[74] Blair. 559.

[75] Padfield. 354.

[76] Blair. 561.

[77] One of the three was a Naval Academy graduate who had resigned his active duty commission prior to World War II, retaining a reserve commission under which he was recalled following Japan’s attack.

[78] Ibid. 772.

[79] Ibid. 561.

[80] Ibid. 857.

[81] Specter. 11.

[82] Ibid. 10.

[83] Ibid. 481.

[85] “In no other type of ship is it so critical that all hands know their jobs and be constantly alert.” CAPT Ned Beach. Beach. 4.

[86] Padfield. 15-16.

[87] Jim Bauer. “Congressman Sinks Submarines” World War II in the Pacific (www.ww2pacific.com/ http://www.ww2pacific.com/congmay.html) 23 Jan 2005.